“ The children are always ours, every single one of them, all over the globe; and I am beginning to suspect that whoever is incapable of recognizing this may be incapable of morality.” –James Baldwin

Mekia Machine is a fierce, inspiring, and visionary abstract figurative artist I met last month at the Blue Gallery in midtown Manhattan. Her life-size portraits of vividly colored overlapping silhouettes punctured my gaze into vast inquiry. Conversation with the stylish and sophisticated Mekia ensued and intensified upon locating common fondness for the watermelon: the incognito symbol of Palestinian resistance. She gets it. I had my 🍉necklace—she her 🍉fan, and out poured human philosophies, reflections on disbelief, and endless lamentation.

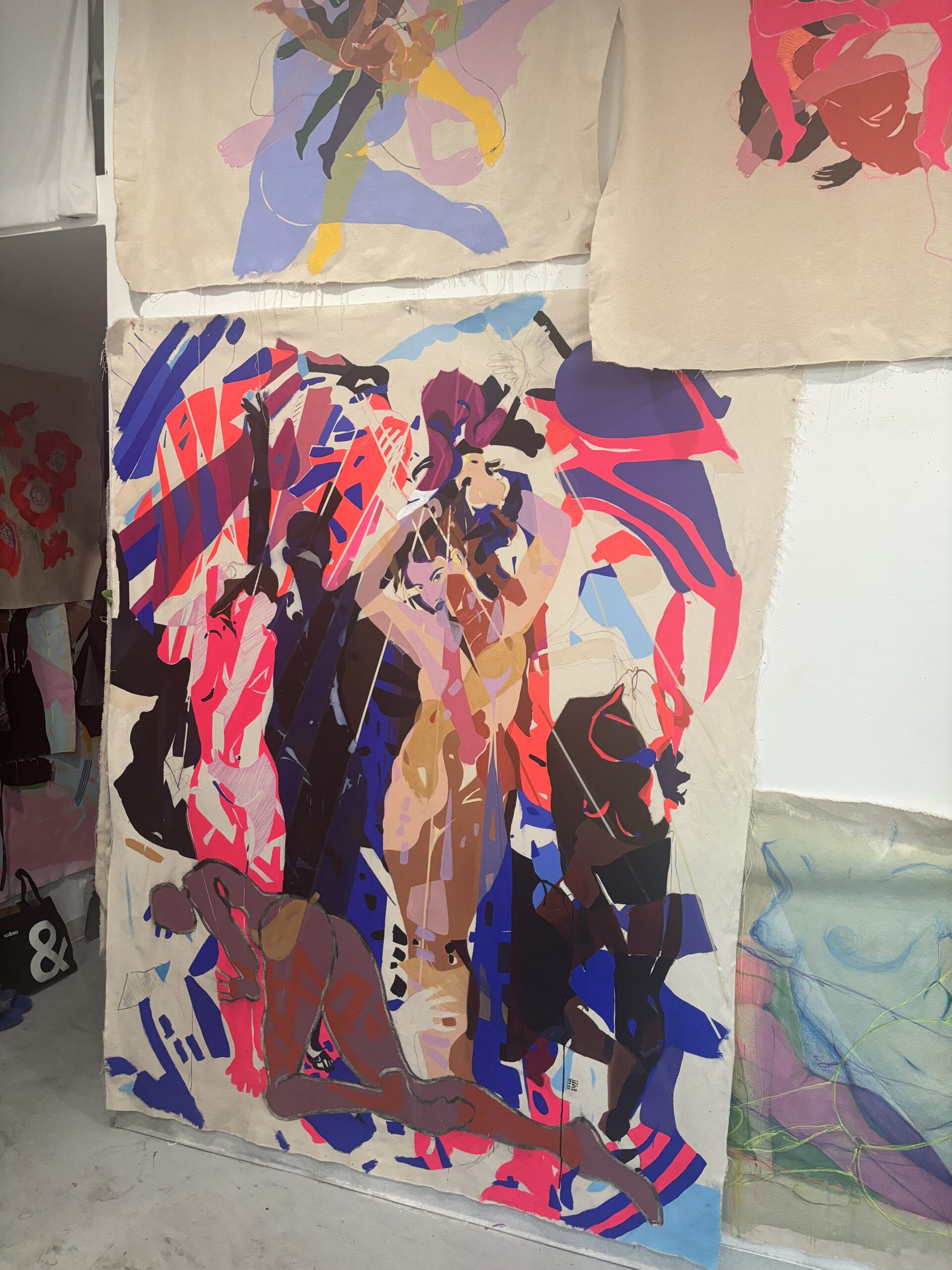

We met in her art studio a few weeks later, close to sunset, where I got to interview Mekia operating holistically in her habitat: a stunning upper Manhattan corner loft with sacred walls canvas-carpeted over like endless montages of memory mixed with matriculated messaging. The artist certainly boasts a gift for endeavoring blending surrealist montage with realistic portraiture. The first emblem I encountered upon entering was James Baldwin quote above.

Subsequently, the multidisciplinary visual artist introduced me to her fledgling series of painting she aims to call “The Children are Ours.” Creating surrealist montages of the real and dreamy, she identifies herself as depicting a go-between of the abstract and the figurative. Expounding on her heartfelt purpose to represent the children, she notes: “I’m constantly thinking about the children [particularly in war zones]: the children in Congo—the children in Palestine. Palestine has been on my mind a lot.” Already on her sixth representation, she aims to continue develop more depictions that are mindful of these children.

“I want to pull these from being overly abstractive to being a moment peering into the real lives of these children without being too realistic…I want them to be cutesy yet graphic.”

***

“What is YOUR process?” I eagerly inquired.

“I’m still figuring out a lot. My process is to really sit with things and to allow it to come because I feel that when I work, there’s premonition involved.”

Starting with sketches, she’ll get all the works up, and then meditatively revisit her original intention. “And then I abstract them,” she enunciates. Diving further inquiry into how one may “reduce human form to simplicity”, while grabbing “the essence rather than mere representation,” Mekia admits to treading bran new brain terrain lately. Especially in lieu of endless ‘dead babies’, and of the plethora of Palestinian novelists she’s been listening to on Libby App via the NYCPL: “I listen to a lot of audio books too. I devour them. Helps me be able to make the work.”

***

Recalling a single image that “changed everything” for her, Mekia admits to not being able to paint for 6 months after:

“It was a photo of a [disfigured Palestinian] child: A CHILD ISN’T SUPPOSED TO LOOK LIKE THAT. It messed with me because I literally just finished a project for a republishing of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein entitled ‘Portrait of The Beautifully Dead, Day’ and ‘Portrait of The Beautifully Dead, Night’. Dr. Frankenstein harvested body parts from the church yard to create his “monster”, so these pieces represent famous beautiful people who died in 2022.”

Seeking to represent the information she’s absorbed alongside the multitude of lives taken, especially babies, her current series is an attempt to “literally harvest these images to create this composite. And I’m like wow—you really dismember bodies at times to see it in reality – and it’s been a lot. How do u turn this off, I feel it because it’s been a lot.” Quite honestly, we all know this feeling. Imploding with recognitions of injustice, the fundamental human truths we value are being reversed, dissolved and topsy-turvy-ed. Everywhere we look, people are inherently racist blind sheep following the most comfortable and familiar crowds of propaganda reaching them.

“I PAINT THE DEAD. How do you document this, you know? I want to say this happened. They were here. They existed. They lived. The focus is on the fact that we are so violent toward babies. We are doing this to children. Adults are doing this to babies.”

By painting the dead, Mekia aims to Remember “the people you’re not supposed to remember, like the heroes who died in battle. Imagine all the women who came before you, whose stories you don’t even know. They existed!” Heretofore, her current mission for “The Children Are Ours” is to make a “placeholder” in lieu of a ‘constellation of these babies’. After all,

“Why should constellations be for all these kings and queens? Like are you kidding me? How any babies have been slaughtered!”

“Like all the stars in the sky—I feel like that’s how close we can get to quantifying it. So, I’ve been thinking about how to create these constellations, and thinking about where they are, and about them being in a different realm.”

Memorializing the Innocent is Mekia’s pivotal focus. After all, her best friend drowned as per her “Dead Lovers #6” masterpiece. “How do you paint a portrait of someone you don’t remember? And how to you paint a portrait of the dead who you DO NOT know?” Resonantly interrogates the mysterious artist. Reiterating her intention to account for the multitudes, she notes: “Compositions tend to be the snapshots in my mind, like if you were to think of a memory and then take a picture of that moment, what does it look like?” Interminably looking for answers, Mekia’s work explores possibilities for how her friend drowned, and how her body felt and dissipated over time in the water. She constructs snapshot visualizations without having all the information—and the same goes for “The Children are Ours” series.

“Just like these images of the babies—I know who some of them are, so I’m trying to be mindful of representing them dead. I do want to represent them as living but it’s hard to make the decision of how to.”

Mekia Machine’s work on babies is a concentric fractalized reflection of her preoccupation with death, dignity, and autonomy, as it extends to women, blacks, immigrants, and one’s forbearers too. After all, ‘how are current Palestinian mothers even having babies that are going into the earth?’ Grappling with the horror these mothers face,“their babies are born then slaughtered, born just to return to the earth.” Further considering ‘black bodies’ or ‘immigrants’ who riskily seek refuge in the countries responsible for their destabilization, and who die trying, Mekia reminds that we are not supposed to remember these people. Such deficit inevitably fuels the justice-seeking visionary.

Conversation ensued about not being able to process it all—generational trauma–scapades. “How do you process it all, there’s just so much to say and think about” the artist laments.

Concurrently developing over the-top-portraits of her grandmother fore-bearers, of whom she has zero photos, Mekia aims to erect them in her likeness: “They are all going to be deities.” Slaves brought over to Jamaica against their will, and the artist humbly recognizes the impossibility of reconciling her perception of them to their actual experienced realities: “Since I don’t have actual photographic evidence of them, I can create them however I want, right?” Aiming to paint the images in the way she sees and feels it, Mekia recognizes that she’s essentially juggling falsified memories. After all, every time you recall something of your past, you do alter it, don’t you?

“All I can think of is the information I have while I’m here and alive—right—I’m seeing you in front of me, but when u leave, I’m going to have this image in my mind of you – but you’re no longer in this physical form…”