Strolling down the streets of Lower Manhattan, Sunday was a day of observation, of immersion in culture, immersion in art. At the South Street Seaport’s Art on Paper, walls were adorned with candy-colored paintings as far as the eye could see. I was honored to receive the privilege of attending the infamous artfair, and of being able to appreciate the immense effort that went into creating such masterpieces. No artist beguiled me as much as H.A. Sigg.

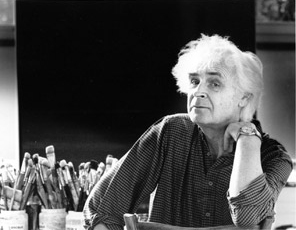

Indeed, the work of Swiss artist H.A. Sigg was a marvel to not only gaze at, but to scrutinize at on a deeper level. His effective use of colors on an abstract plane bedazzled me, to the point that I wanted to learn more–to uncover his secrets, his motivations, his driving force. As I researched information on the man himself, I unearthed a wealth of analysis.

Born in 1924 in Zurich, Switzerland, Hermann Alfred Sigg studied at the School of Applied Art in Zurich, then going on to attend l’Academie Andre’ Lhorte in Paris, France. In the 1960s, Sigg developed a style that according to Amy H. Winter used abstraction to represent nature. According to Winter:

“Sigg’s abstract handling of form, light and color stood in for the aesthetics of nature itself (subsequently developing into abstract signs of nature, culture, and the self).”

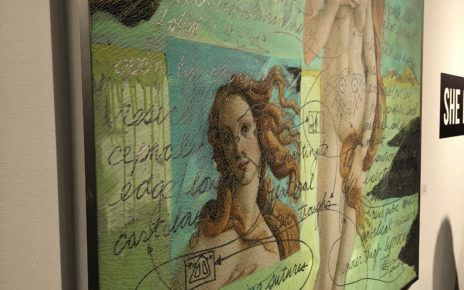

From the paintings I observed, I had a solid grasp of Sigg’s preference for the geometric, for that which only looked to inspire the basest of emotions and thoughts. Winter makes it clear that Sigg is a minimalist whose tastes for abstraction supersede any desire to fulfill specific requirements of detail.

When I observed the paintings, I definitely could feel a sense of this use of abstraction. One particular painting that I felt emphasized this well was Untitled #2 from 2001. The painting contains several boxes of varying shades of blue, with a box in the middle being white with a black snake like creature within the middle of the white box. Although Sigg used only the most rudimentary of shapes for this painting, the feeling of a somber, wistful winter’s night was immediately evoked. This ties perfectly into the analysis of Winter, who states:

“But there are no mountains, and there are no clouds or overlapping near-, middle- or far-distances in Sigg’s landscapes, no mathematical perspective to fix or focus our gaze. Instead, at first sight, there is a beautiful minimal image, a hallmark of modern abstract painting that stresses and experiments with the flatness of the picture plane to create a new ethos of “painting for painting’s sake.”

Winter makes it clear that while Sigg’s paintings do not contain a high amount of detail, they don’t have to be considered a lesser form of art than more detailed works are. It’s the emotions that the painting invokes inside of the observer that determine whether or not they have artistic validity.

Another painting by Sigg that I felt emphasized his devotion to simple geometric shapes that leaned toward the abstract is Untitled #1 from 2000. This painting uses several shades of brown and blue that give the impression that the viewer is looking overhead of a lake. Though this cannot be determined with the utmost certainty, there is enough composition and effective use of color palette and contrast to evoke such a feeling.

Colors such as brown and blue when used in conjunction with each other tend to give off a topographic type of feeling, which Sigg effectively did here.

I was honored to have attended Art on Paper, and even more honored to have observed HA Sigg’s work in close detail. While I initially was enamored by the aesthetics of his work, studying interpretations of it led me to see the power that the simple use of geometric shapes can have in conveying larger ideas. For that, Sigg’s work is worth studying whether a seasoned painter or a casual fan of the medium.